- By Vivek Tiwari

- Fri, 08 Aug 2025 05:24 PM (IST)

- Source:JND

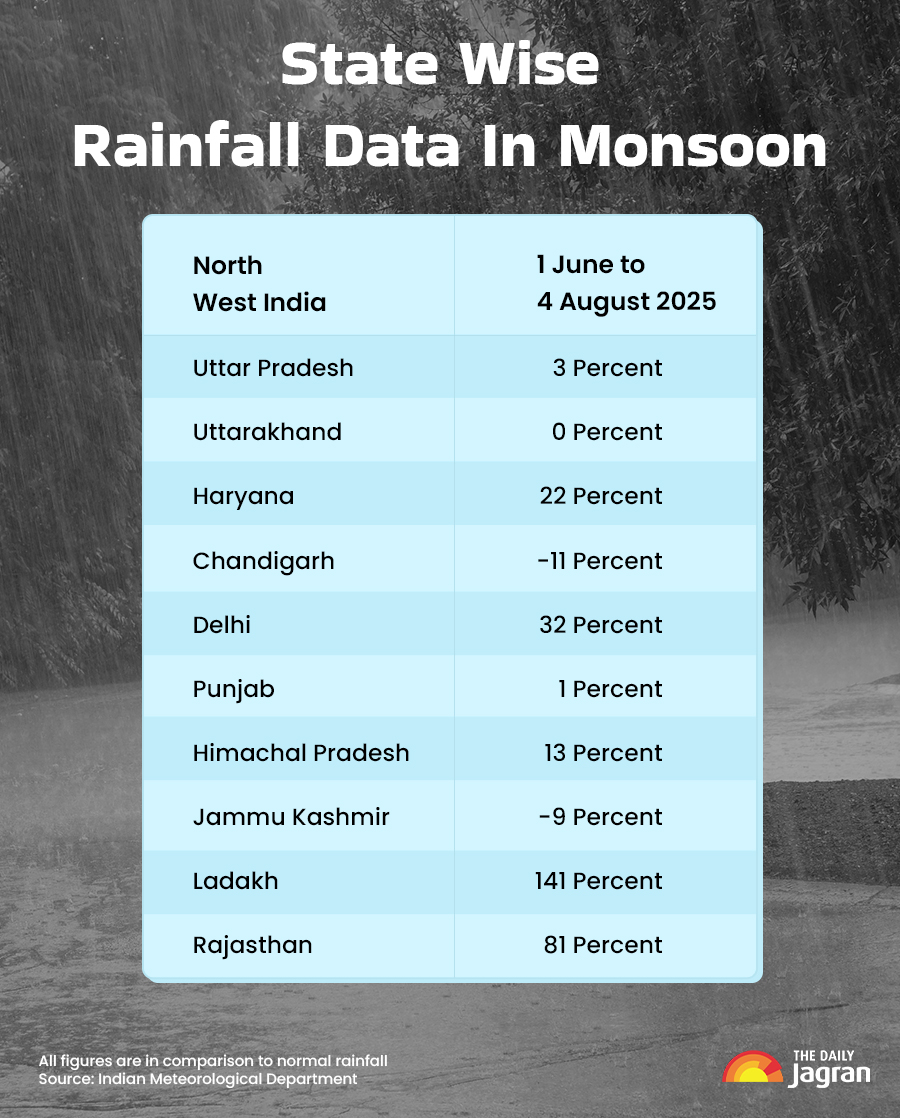

Due to climate change, the monsoon pattern has shifted. This year again, the trend of the monsoon is markedly different. While regions such as Meghalaya, which have lived under the shadow of clouds for years, have received up to 48 per cent less rainfall so far, a traditionally dry region like Rajasthan has recorded up to 81 per cent more rainfall than normal. This reversal in rainfall trends has raised alarm bells on every front, from agriculture to water security and biodiversity, making it clear that climate change is no longer a distant warning, but a reality knocking at our doorstep.

According to a study conducted by the Meteorological Department, states that have received heavy rainfall over the last three decades, such as Meghalaya, Nagaland, West Bengal, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh, have now seen a significant decline. Meanwhile, a study by the Max Planck Institute warns that such changes in monsoon patterns will become even more pronounced in the future. In Rajasthan, monsoon rainfall is projected to rise by up to 35 per cent between 2020 and 2049.

Meghalaya, located in Northeast India and literally meaning ‘the abode of clouds’, is now experiencing reduced rainfall. The state is home to two of the wettest places on Earth — Mawsynram and Cherrapunji — and 83 per cent of its population depends on rain-fed agriculture. But the continuous drop in rainfall has become a matter of concern.

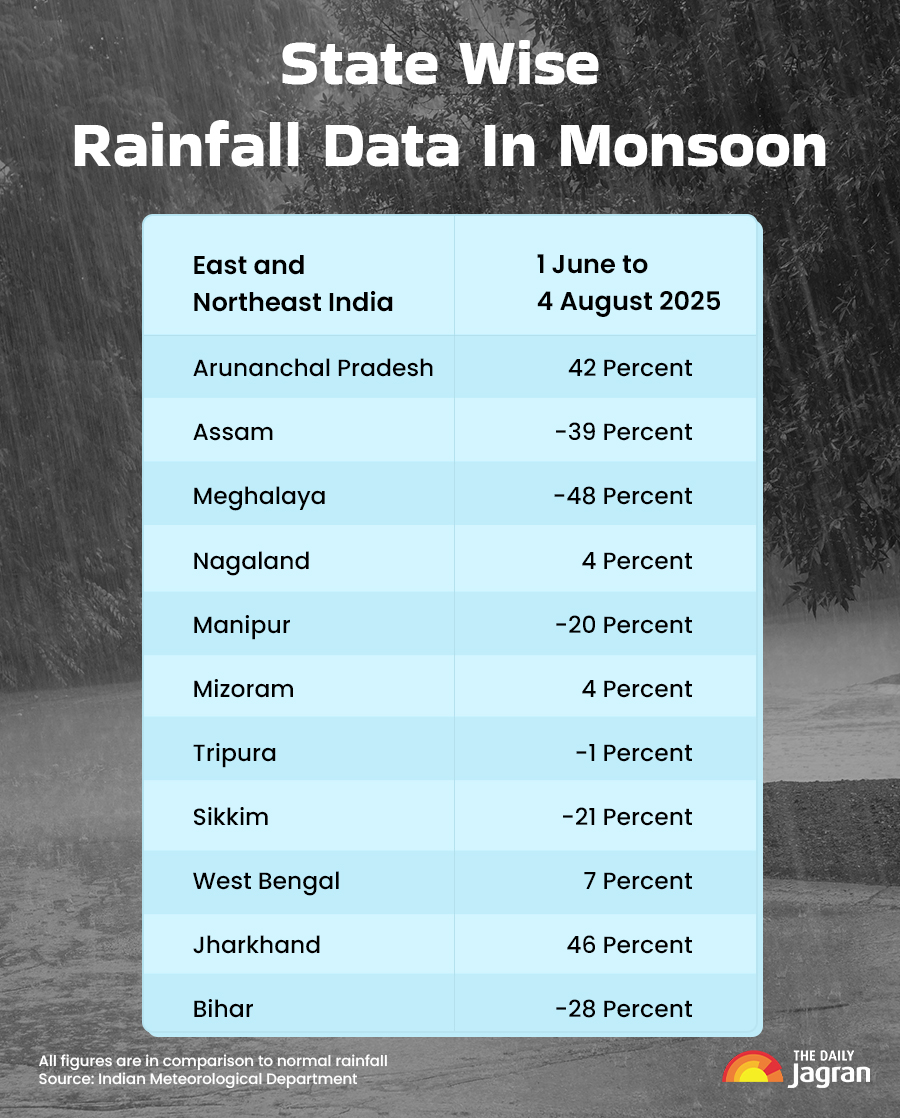

From June 1 to August 4 this year, the state has recorded 48 per cent less rainfall than normal. Arunachal Pradesh has seen 42 per cent less, and Assam 39 per cent less rainfall. In sharp contrast, the relatively dry states of Jharkhand and Rajasthan have recorded 46 per cent and 81 per cent more rainfall than average, respectively.

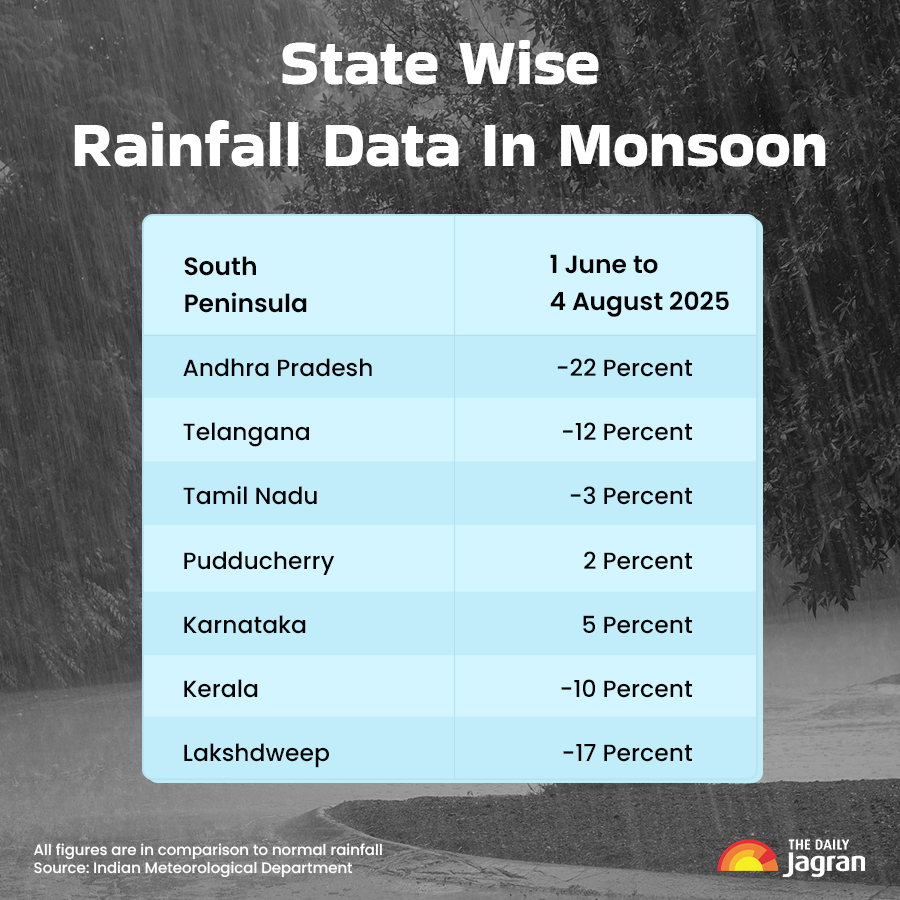

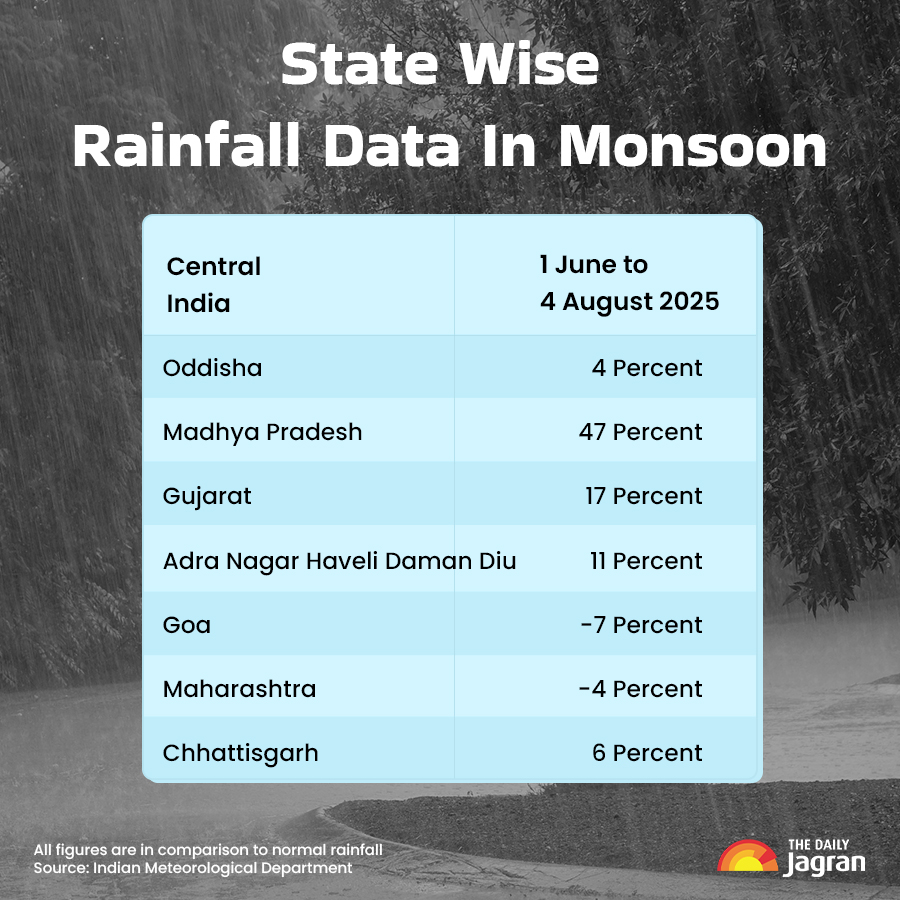

A report by the public policy think tank CEEW shows that patterns of both the Southwest and Northeast monsoons have changed over the last decade. Data from 2012–2022 reveals that 55 per cent of the country’s tehsils have recorded an increase in Southwest Monsoon rainfall, while 11 per cent have seen a decline of more than 10 per cent compared to the climate baseline (1982–2011). Tehsils in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Central Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu, regions traditionally known for dry conditions, have recorded a rise in rainfall.

Experts say that due to a warming climate and rising sea temperatures, rainfall along India’s western coast is likely to increase further in the future. Given these changing rainfall patterns, adjustments in crop varieties and cropping cycles will be essential for ensuring future food security.

This year, due to the influence of La Niña, heavier rainfall has been predicted. However, it is the western coastal and adjoining regions, parts of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh, that have received far more rain than normal. The study also found that in the last decade, 55 per cent of tehsils saw an increase in Southwest Monsoon rainfall. In traditionally drought-prone areas of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Central Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu, rainfall has risen sharply.

Traditionally, India’s monsoon season ran from June 1 to September 30. But the study shows that in recent years, the withdrawal of the monsoon has slowed considerably, with rainfall continuing in many parts of the country well into October and November. This is another clear sign of changing monsoon behaviour.

In India, the monsoon season was considered to be from June 1 to September 30. But in our study, we have found that in the last few years, the pace of the monsoon's withdrawal has been becoming extremely slow. Often, rain continues in many parts of the country even in October and November. This is a result of the changes in the monsoon's pattern.

Meteorologist Samarjeet Chaudhary explains that due to global warming, the monsoon pattern has shifted. “Earlier, when the monsoon arrived, the northeastern states and coastal areas would receive heavy rain. But over the last decade, rainfall in the northeast has dropped sharply — especially in Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, and the Terai regions of West Bengal,” he says.

On the other hand, central India, including Rajasthan and Gujarat, has been receiving well above-average rainfall. Climate change has also led to more frequent incidents of cloudbursts and extreme rainfall in the hilly states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand — a trend expected to accelerate. Research by the Max Planck Institute estimates that between 2020–2049, rainfall in Western Rajasthan could increase by 20–35 per cent, and in Eastern Rajasthan by 5–20 per cent, compared to data from 1970–1999.

A research paper published in the journal ScienceDirect has also found that the “monsoon line”, the primary belt of monsoon rainfall, has shifted by up to 10 degrees due to climate change. This means the rain belt can move significantly northward or southward depending on the shift, impacting agriculture and water availability in the affected areas.

Dr Prem Chand Pandey, former Director of the National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research (NCAOR), warns that global warming has caused sea surface temperatures to rise, warming ocean waters to depths of up to 300 metres. This has sharply increased the frequency of cyclones. “If immediate steps are not taken, the challenges for people living in coastal areas will grow significantly,” he says.

As sea temperatures rise, not only do cyclones occur more frequently, but their intensity also increases. Warmer seas fuel stronger winds and heavier rainfall during cyclones, often causing flood-like situations in coastal areas.

Over the past decade, cyclone forecasting technology has become far more advanced, enabling more accurate predictions of cyclone intensity and faster evacuation efforts, saving countless lives. However, improving landfall location forecasts remains an important challenge.

Prepare for climate change

Vishwas Chitale stresses that with changing weather, we must adapt in time. The monsoon is the lifeline of Indian agriculture, and with shifting rainfall patterns, farming practices must also evolve to ensure food security.

In states like Rajasthan and Gujarat, where low-water crops were traditionally grown, farmers may now need to shift to varieties that can utilise the increased rainfall. Similarly, in states where water-intensive crops like rice were once favoured, varieties requiring less water may need to be considered.

( This article was translated for The Daily Jagran By Akansha Pandey.)