- By Shivangi Sharma

- Sat, 12 Oct 2024 03:55 PM (IST)

- Source:JND

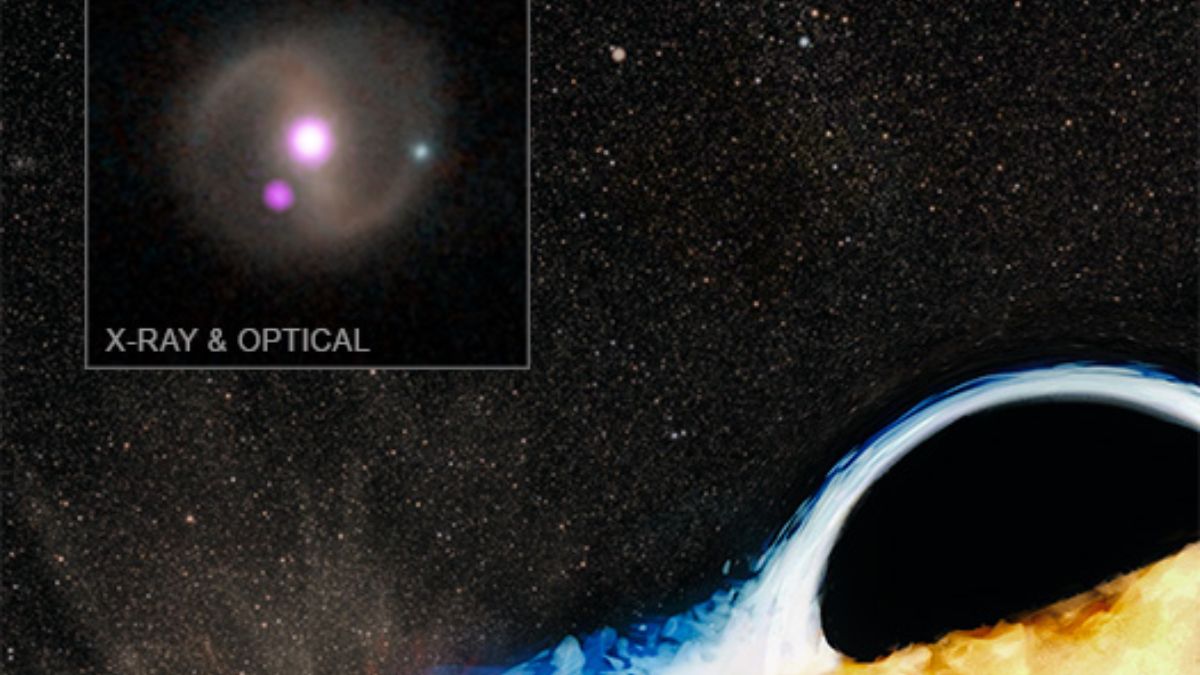

In a shocking discovery, a massive black hole has destroyed one star and is now using the debris to strike another star or a smaller black hole that was previously unaffected. This discovery was made using NASA’s space observatories Chandra, HST, NICER, Swift, and ISRO’s AstroSat, according to a statement from the Indian space agency.

"It gives astronomers important insights, connecting two mysteries where there were previously only suggestions of a link," said ISRO, which is based in Bengaluru.

In 2019, astronomers observed the signal of a star that ventured too close to a black hole and was destroyed by its intense gravitational pull. The remnants of the star formed a disk around the black hole, creating what can be described as a stellar graveyard.

ALSO READ: Sahara Dessert Sees First Flood In 50 Years, NASA Shares Dramatic Images | See Pics

Scientists have documented numerous instances where objects come too close to a black hole and are torn apart in a single burst of light, known as "tidal disruption events" (TDEs).

In recent years, a new class of bright flashes from galaxy centres has been discovered, visible only in X-rays and repeating frequently. These events, linked to supermassive black holes, were difficult for astronomers to explain, so they named them "quasi-periodic eruptions" (QPEs).

Ultraviolet Data Reveals Size Of Disk Around Supermassive Black Hole

“This is a significant advancement in our understanding of what causes these regular eruptions,” said Andrew Mummery from Oxford University. “We now understand that we need to wait a few years for the eruptions to begin after a star has been destroyed, as it takes time for the disk to expand enough to collide with another star.”

In 2023, astronomers used both the Chandra and Hubble telescopes to study the remnants left after a tidal disruption event had concluded. Chandra collected data over three observations, spaced 4 to 5 hours apart. The total observation time of around 14 hours revealed a weak signal during the first and last sessions, but a significantly stronger signal in the middle one.

Simultaneous ultraviolet data from Hubble allowed scientists to estimate the size of the disk surrounding the supermassive black hole. They discovered that the disk had grown large enough that any object orbiting the black hole in roughly a week or less would eventually collide with the disk, triggering eruptions.